As an educator with a deep desire to help struggling students and their families, I used to imagine myself as a rescue worker parachuting into a disaster zone, knapsack stuffed full of answers and fail-safe strategies, energy bars, band-aids, and waterproof matches. I was good at what I did because I worked tirelessly, giving everything to each of my students. But if my plan failed, or I didn’t have the necessary tool in my knapsack, I blamed myself, rather than understanding failure as simply an obstacle, an important piece of data, an opportunity for reevaluation and reciprocal growth. This perfectionist mindset didn’t allow for the growth and reciprocity I’ve come to see as crucial to a successful and empowering coach-student relationship, one that values process over results and long term fulfillment over individual achievements or products.

My change in thinking evolved over time, but the real turning point was when my perfectionism came up against the all the messy challenges of parenting. When I failed to deliver a consistent consequence, put the wrong kiddo in time-out, arrived late at the pick-up line, or sent someone off to school without brushed hair—oy!—each little failure ate away at this mama’s heart! And as I learned to navigate my son’s ADHD diagnosis, I was forced—or freed, really—to forgive myself for the hiccups and the constant need to adjust the plans, and accept our challenges as adventures.

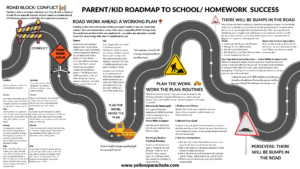

Learning how to parent wholeheartedly made me a better, more flexible, dynamic, and empathetic educator—and helped me have more fun! Rather than beating myself up when one method or explanation stopped working, I began to understand that adjustments and reevaluations are an important part of learning and growth. With ADHD, lots of things work for a short time. The ADHD brain gets bored with routine; introducing new routines, sometimes called the “same but different” approach, continues to create novelty that can help hold a child’s interest.

Jumping Together

Developing the Student Operating System (SOS) curriculum has enabled me to articulate the healthier vision I’ve come to embrace through decades of this work—that is, the coach as jump instructor rather than rescue worker. The coach as jump instructor understands that the fall is the journey, that working through failure and struggle is what allows us to grow into our full potential. We can’t as humans, even as parents and professional educators, avoid the fear or pain of the fall ourselves, much less save our students and children from it, but we can provide the guidance and emotional support—the tools—for a safe landing. We can say we’re in this together. And of course, it’s not all about pain, either. Skydiving is fun (so say some—gulp)! When we stop fighting the fall, we can embrace the thrill of it—”yeehaw!” we shout, tumbling, stumbling into our dreams.

The coach as jump instructor understands that a successful jump requires a trusting, dynamic, empathetic relationship between instructor and student—that is, a relationship of reciprocity. I don’t come with a single shiny proven method, or a magic wand I can wave and say “troubles be gone” (though that sounds exceedingly lovely—someone please pass that red cape), but I will be there beside you, leaning in, asking questions, getting gritty, and helping you find your own answers.

Reciprocity says: I see you. I value your experience, your unique strengths and struggles and fears and passions, and I will work with you to develop a path forward that honors who you are and where you are. I won’t grab you and strap you into the parachute if you’re petrified of heights, and I won’t coach you through breathing techniques to calm your anxiety if you’re excited to throw yourself out of the plane. And as we fall together, I will watch you move, attend to your joy and your anxiety, to plan our next moves together. Are we ready to try somersaults, or are we practicing holding still in the air? Feedback from you tells me my next move.

Unlearning the “naturalness bias,” and getting up again

The bias to see struggle, or falling, as shameful is deeply ingrained in us on a subconscious level, even as we can recognize its absurdity. We don’t say to a first-year medical student—”you’re so bad at brain surgery!” before she’s ever touched a scalpel, just as we don’t berate a two-year-old for not knowing how to swim (or for that matter, an any-year-old who’s never had the chance to learn). None of us are born knowing how to skydive, not even those will go on to become jump instructors ourselves, and yet when faced with extraordinary achievement, we gawk and say—what a natural! What innate talent!

Everything worth doing, we acknowledge, requires effort and yet our behaviors do not necessarily reflect our beliefs. Angela Duckworth defines the “naturalness bias” as: “a hidden prejudice against those who’ve achieved what they have because they worked for it, and a hidden preference for those whom we think arrived at their place in life because they’re naturally talented.” Psychology studies have shown that despite outward praise of effort and hard work, Americans consistently rate musicians perceived as naturally talented as more skilled than those perceived as “strivers” who worked hard to hone their skills, and that entrepreneurs seen as “naturals” are funded at a greater rate and for more money than those seen as “strivers.”

This bias does a disservice both to those perceived as talented, and those who struggle. People we perceive as “naturals”—Olympic athletes and world-class musicians—have in fact spent hours and hours, years and years, honing their skills. And their success depends not just on their own hard work, but on the opportunities and support that enabled them to pursue their passions—the parents who could afford swim lessons; the encouraging coaches; the academic tutors—in other words, the parachute that supported them through their journeys to greatness.

As the sociologist Dan Chambliss, author of a study of competitive swimmers called “The Mundanity of Excellence,” writes: “Superlative performance is really a confluence of dozens of small skills or activities, each one learned or stumbled upon, which have been carefully drilled into habit and then are fitted together in a synthesized whole.”

It was Duckworth’s own experience as a seventh-grade math teacher, watching talented students slip behind their less naturally gifted but hard-working peers, that lead her into her groundbreaking study of grit. She recounts her revelation in the chapter “Distracted by Talent:” “When I taught a lesson and the concept failed to gel, could it be that the struggling student needed to struggle just a little bit longer? Could it be that I needed to find a different way to explain what I was trying to get across? Before jumping to the conclusion that talent was destiny, should I be considering the importance of effort? And, as a teacher, wasn’t it my responsibility to figure out how to sustain effort—both the students’ and my own—just a bit longer?”

As an educator, my answers to Duckworth’s questions are yes, yes, a thousand times yes! This is the crux of why one-on-one work with a YP Learning Coach works. We join our students in their struggle so they feel safe and supported. By sustaining our own efforts, along with a sense of adventure and fun, we guide our students to create meaningful connections with learning. By our own examples, we show them that the joy is in the struggle, the effort. We empower students to give their best effort by developing a relationship in which we meet their grit with our own, step by step, lesson by lesson. It’s relationships + science at their best!

-Cara